Latest News at PER

These are the top 10 private equity firms everyone wants to work for

18 Apr 2017

By Paul Clarke efinancial careers

Private equity is all about aspiration. Most investment bankers covet a buy-side role early on in their career, but only a very select few make it in.

“We have 2,500 applications every month,” says Gail McManus, managing director of PER, Private Equity Recruitment. “We place 200 people a year.”

In other words, even if you’re among the 2-4% of applicants who end up in a front office banking job, there’s still just then a 0.7% chance of getting into private equity.

“If you’re interviewing for a private equity job, there are likely to be another 100 people who made the shortlist,” says McManus.

Junior bankers have started to get creative break into the buy-side. This year, they’ve been targeting smaller private equity firms or VC funds, or have moved into areas like direct lending or distressed lending funds to make the switch.

But it’s the big private equity companies that remain the most desirable. Blackstone Partners is the PE firm that most finance professionals want to work for, according to the 2017 eFinancialCareers Ideal Employer rankings. KKR and The Carlyle Group took second and third places respectively in this year’s rankings.

Aside from (slightly) better work-life balance than investment banking, private equity firms have one key thing going for them – carried interest. This is the share of any profits a manager receives, which usually benefits the most senior staff at the firm. However, now that most big private equity firms have both analyst and associate recruitment programmes, it’s becoming increasing common to offer carry to even the most junior ranks.

The appeal of big earning power in private equity is reflected in our rankings. 85% of people who voted for Blackstone believe that a competitive salary is on offer, and 87% would want it if they went to work for them. 81% also anticipate a big bonus, and 89% of respondents said it was important to them.

A higher proportion of people who voted for Goldman Sachs expected a large salary than at any other investment bank, but this was 82%, while 76% want a competitive bonus.

Analyst pay in private equity averages out at $114k on average in the U.S, according to figures from Preqin. This is on a par with junior pay in banking, but it’s later on when the buy-side starts to pull ahead on pay. Managing directors/partners can earn $3.3m in carried interest alone, the Preqin figures suggest, compared to around $1.1m in total compensation for a managing director in investment banking.

Private equity firms have become warier of potential recruits just chasing a big pay day, however. Terra Firma founder Guy Hands said recently that they’d cut graduate salaries by 50% and eliminated bonuses, in order to dissuade the sort of applicants that might also be looking for high salaries at investment banks. The sweetener, however, was that the firm would pay for a deposit on a house in London if the new recruits lasted five years.

Perhaps it’s also the nature of the work that appeals to people who want to work in private equity. 75% of respondents who voted for Blackstone said challenging and interesting work was a strength of the firm, and 86% said it was important to them. This is higher than all the top banks in our ranking – 70% of those who chose J.P. Morgan expected the same, for example. It also only just lagged the ever-innovative Google, which had 77% of voters saying interesting work was a reason they wanted to work there.

“The whole concept of being the person who invests in something and helps it grow is an appealing aspect of the job, and not something many young people get to experience,” says McManus. “It takes judgement, technical skill and responsibility – and it’s hard. This is the reason so many people fail to make the cut.”

It also helps that while investment banks are trigger happy, private equity firms rarely fire people in large numbers. Their investment teams remain relatively small – typically around 30 people in regional teams, even in a large private equity firm – and they’re seen as stable employers. 74% of those who voted for Blackstone said financial performance of the firm was a strength. Again, this was higher than all the top investment banks in our ranking.

Still, private equity firms also had the same weaknesses as investment banks. Just 9% of people who chose KKR said they expected manageable working hours, 16% of Blackstone voters and 13% of those who named The Carlyle Group as their employer of choice said the same.

Similarly, private equity firms might be seen as challenging places to work, but they’re not perceived as being innovative. 37% of Carlyle Group voters, and 45% of those who chose KKR said that the firms were innovators. Blackstone led the group here, with 52% of voters saying they thought the firm was an innovator in the industry.

Private equity firms might not be short of applicants, but there’s still a mismatch between candidate desires and what they believe the buy-side can offer. 39% of people who chose Blackstone said decent working hours were important to them, and 27% of KKR voters said the same. Similarly, 64% of Blackstone respondents said they’d like to work for an innovative company. 65% of KKR voters and 69% who chose Carlyle Group also said this.

The growing appeal of sovereign wealth funds

Sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) get a bad press. They’re seen as overly-bureaucratic, poor payers and are often located in parts of the world far away from major financial centres. Yet, one of the big trends in our private equity rankings this year is the growing appeal of SWFs. GIC, the government of Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund, ranked fourth this year. But Temasek, another Singapore SWF, and the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA) also made the top 10.

People who voted for these firms remain realistic about what they can expect by working there, however. At GIC, for example, just 65% of people said they anticipated a big salary by working for the sovereign wealth fund, and 57% said they expected a competitive bonus. One of the big appeals of these organisations is simply that they have large investment teams and continue to search in London and New York for the investment talent they need. ADIA, for example, has around 1,700 people employed globally and Temasek has a headcount of 530. Considering the competitive nature of private equity jobs, maybe this is enough.

“We have 2,500 applications every month,” says Gail McManus, managing director of PER, Private Equity Recruitment. “We place 200 people a year.”

In other words, even if you’re among the 2-4% of applicants who end up in a front office banking job, there’s still just then a 0.7% chance of getting into private equity.

“If you’re interviewing for a private equity job, there are likely to be another 100 people who made the shortlist,” says McManus.

Junior bankers have started to get creative break into the buy-side. This year, they’ve been targeting smaller private equity firms or VC funds, or have moved into areas like direct lending or distressed lending funds to make the switch.

But it’s the big private equity companies that remain the most desirable. Blackstone Partners is the PE firm that most finance professionals want to work for, according to the 2017 eFinancialCareers Ideal Employer rankings. KKR and The Carlyle Group took second and third places respectively in this year’s rankings.

Aside from (slightly) better work-life balance than investment banking, private equity firms have one key thing going for them – carried interest. This is the share of any profits a manager receives, which usually benefits the most senior staff at the firm. However, now that most big private equity firms have both analyst and associate recruitment programmes, it’s becoming increasing common to offer carry to even the most junior ranks.

The appeal of big earning power in private equity is reflected in our rankings. 85% of people who voted for Blackstone believe that a competitive salary is on offer, and 87% would want it if they went to work for them. 81% also anticipate a big bonus, and 89% of respondents said it was important to them.

A higher proportion of people who voted for Goldman Sachs expected a large salary than at any other investment bank, but this was 82%, while 76% want a competitive bonus.

Analyst pay in private equity averages out at $114k on average in the U.S, according to figures from Preqin. This is on a par with junior pay in banking, but it’s later on when the buy-side starts to pull ahead on pay. Managing directors/partners can earn $3.3m in carried interest alone, the Preqin figures suggest, compared to around $1.1m in total compensation for a managing director in investment banking.

Private equity firms have become warier of potential recruits just chasing a big pay day, however. Terra Firma founder Guy Hands said recently that they’d cut graduate salaries by 50% and eliminated bonuses, in order to dissuade the sort of applicants that might also be looking for high salaries at investment banks. The sweetener, however, was that the firm would pay for a deposit on a house in London if the new recruits lasted five years.

Perhaps it’s also the nature of the work that appeals to people who want to work in private equity. 75% of respondents who voted for Blackstone said challenging and interesting work was a strength of the firm, and 86% said it was important to them. This is higher than all the top banks in our ranking – 70% of those who chose J.P. Morgan expected the same, for example. It also only just lagged the ever-innovative Google, which had 77% of voters saying interesting work was a reason they wanted to work there.

“The whole concept of being the person who invests in something and helps it grow is an appealing aspect of the job, and not something many young people get to experience,” says McManus. “It takes judgement, technical skill and responsibility – and it’s hard. This is the reason so many people fail to make the cut.”

It also helps that while investment banks are trigger happy, private equity firms rarely fire people in large numbers. Their investment teams remain relatively small – typically around 30 people in regional teams, even in a large private equity firm – and they’re seen as stable employers. 74% of those who voted for Blackstone said financial performance of the firm was a strength. Again, this was higher than all the top investment banks in our ranking.

Still, private equity firms also had the same weaknesses as investment banks. Just 9% of people who chose KKR said they expected manageable working hours, 16% of Blackstone voters and 13% of those who named The Carlyle Group as their employer of choice said the same.

Similarly, private equity firms might be seen as challenging places to work, but they’re not perceived as being innovative. 37% of Carlyle Group voters, and 45% of those who chose KKR said that the firms were innovators. Blackstone led the group here, with 52% of voters saying they thought the firm was an innovator in the industry.

Private equity firms might not be short of applicants, but there’s still a mismatch between candidate desires and what they believe the buy-side can offer. 39% of people who chose Blackstone said decent working hours were important to them, and 27% of KKR voters said the same. Similarly, 64% of Blackstone respondents said they’d like to work for an innovative company. 65% of KKR voters and 69% who chose Carlyle Group also said this.

The growing appeal of sovereign wealth funds

Sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) get a bad press. They’re seen as overly-bureaucratic, poor payers and are often located in parts of the world far away from major financial centres. Yet, one of the big trends in our private equity rankings this year is the growing appeal of SWFs. GIC, the government of Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund, ranked fourth this year. But Temasek, another Singapore SWF, and the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA) also made the top 10.

People who voted for these firms remain realistic about what they can expect by working there, however. At GIC, for example, just 65% of people said they anticipated a big salary by working for the sovereign wealth fund, and 57% said they expected a competitive bonus. One of the big appeals of these organisations is simply that they have large investment teams and continue to search in London and New York for the investment talent they need. ADIA, for example, has around 1,700 people employed globally and Temasek has a headcount of 530. Considering the competitive nature of private equity jobs, maybe this is enough.

By Paul Clarke efinancial careers

What influence can Napoleon the pig have had on private equity?

03 Feb 2017

John Cockburn, Consultant at PER, sums up the sentiments of the panelTaking centre stage at the Real Deals Mid-Market PE event for the second panel session of the day were Jeremy Hand of Lyceum Capital, Hamish Mair of BMO Global Asset Management and Andrew Hartley; alongside Gail McManus, Managing Director of PER.

The topic: “Animal Farm – when some partners are more equal than others: Best practice in incentivisation, retention and succession”.

Chaired by Nicholas Neveling of Real Deals, the discussion involved a lively conversation on the trials and tribulations faced by founding partners when planning succession within their funds, and how the carried interest system can be an excellent incentive for some people, but also a handcuff for others.

The consensus amongst the panel around succession was that larger fund managers who have branched out from a traditional PE fund-based structure find it much easier to manage succession. This is a model that stems from the US and hasn’t been adopted yet by the majority of funds in Europe.

For those traditional partnerships, where founding partners have gone through a lot of pain in the beginning setting up funds for the first time, it can be harder to let go and hand over the gain which comes afterwards. It was agreed the best way to achieve a smooth transition is to plan far ahead, in the same way that succession within portfolio companies is planned before exiting.

This is never easy, but can be aided when there is a natural progression, for example when there is a spread of age and experience amongst the partners.

When it comes to retention and incentivisation the major focus was on carried interest, although the split of management fees also cropped up as a question from the audience.

Gail pointed out that it doesn’t benefit anyone when people are in the wrong job. This is where carry can be a restrictive factor, tying people into roles where nobody is happy. A slight chuckle could be heard when the idea of a “transfer window” was raised, although more than one person could be seen contemplating it thoughtfully…

The difference of opinion between LPs and GPs on carry was noticeable, and sparks almost started to fly when the conversation moved onto the comparison of the benefits of deal-by-deal allocation and traditional end-of-fund distribution.

Peace was reached with the introduction of new ideas. One suggestion to keep GPs happy with early returns for their efforts but also to placate LPs (who don’t want to watch managers whose funds implode after early success escape with carry they don’t deserve) was to introduce funds of shorter lifespans. The objection to this of course is the need for more regular fundraising.

As attractive as carried interest appears to be, Andrew pointed out that since PE began in the 80’s, over 50% of funds have not achieved carry. Therefore there can be a lot of angst over distribution of carry during, and prior to, the fund’s lifetime which could very well be pointless in the long run.

The over-arching theme for the whole panel was that in order to achieve success in incentivisation, retention and succession there has to be open and frank dialogue between everyone involved. Whether that be when allocating carried interest, dispersing management fees or indeed arranging a plan for who takes over and when, the best approach is one that involves the same depth of forethought and planning used when successfully investing in businesses.

About the author: John Cockburn joined PER after nine years as an officer in the British Army. He now works on placing people into investment, IR and origination roles across the middle market.

Breakfast Seminar

05 Dec 2016

30 senior private equity professionals debated the issues around promoting and retaining females at PER's breakfast briefingJohn Cockburn, Consultant at PER

An expectant hush fell across the room. Flakes of pastry fell from still lips to flutter to the ground like the cast-off plumage of a delicate, golden, songbird. All eyes turned towards the front of the room, where the managing director of PER, Gail McManus, was ready to introduce the guest speaker - Jeryl Andrew - the new CEO of Level 20. Jeryl has been an investor with Abingworth, Vencap and Advent Ventures and so knows first-hand the difficulties that women face in reaching senior positions within funds.

Gathered together for this breakfast meeting and presentation were professionals from across the Private Equity and Venture Capital industry. The topic: "Retaining and Promoting Females". One might expect the room to be entirely women, but this wasn’t the case at all. A great mix of both sexes had turned up to hear from the lady who has taken the helm at the organisation that is dedicated to increasing the amount of females in senior private equity positions across Europe to 20% by the year 2020.

According to the recent gender survey conducted by PER, only 7% of the most senior positions within 100 funds are held by women (this can be compared to the FTSE 100, where women hold 26% of all executive board positions*). Of those 100 private equity funds, only 20 actually have women in top roles – 80% have no women at that level at all.

Since its inception, Level 20 has increased its membership to over 600 people – both men and women – and has received sponsorship from 36 GPs (ten of which were represented at this meeting).

The crux of the presentation was to describe the steps that Level 20 is taking to reach its goal. The organisation has three main programmes: Networking, Mentoring and Philanthropy. Jeryl concentrated on explaining the Mentoring programme, which was first piloted last year and has been expanded this year due to its success.

The programme paired 23 principal level female investors with senior mentors (five of whom were men) who then embarked on a year-long programme with five or six planned meetings where issues could be discussed privately and maturely. There was also a series of breakfast meetings to assist in developing “soft” skills such as building networks, personal presentation and the principles of coaching and mentoring.

This year there are 25 pairs of senior and mid-level professionals, including 14 senior male mentors, and 19 pairs of mid-level mentors and junior mentees. Several of the mid-level mentors are people who were mentees under the pilot programme. The programme of events has also been expanded, to include “hard” skill training as well, such as negotiation techniques.

Jeryl was very open that Level 20 are always looking for ideas on how to expand the programme, and are very receptive to suggestions.

The most important thing for the success of Level 20’s objective of inspiring more women to join and succeed in private equity is for more firms and funds to support Level 20 and its work. Convincing people it’s a worthy aim is relatively easy, but convincing them to take an active part is more difficult.

In order to support their work, and possibly identify the issues around the stumbling blocks faced by women in their careers, Jeryl and the team are in discussions with Judge Business School to commission a research project determining the career paths of 1000 PE/VC professionals of both sexes. There’s nothing like hard data to prove a point.

Jeryl opened up the discussion to the floor, to see what different funds have experienced, how they are tackling the issue themselves, and if they had any “lessons learned” they could share.

The response was lively and informed; Zoe Lockwood of Cinven Partners, who is on the HR Advisory Council for the Level 20 mentoring project, brought up the point that the male mentors on the pilot programme had learned a huge amount by taking part. For example, some became aware that the unconscious bias that affects women on a day-to-day basis was creating a situation where women are hesitant to show their passion and ambition openly, for fear of being seen as aggressive.

Luke Jones, a Partner at MML Capital Partners, suggested that the best way of increasing the numbers of females at the top was to expand the funnel at the bottom. What makes his point different to what you may have heard before though, was the suggestion that the industry as a whole engages earlier with potential candidates, and maybe works alongside the Big Four and the banks to create training routes. Level 20 has already started addressing this using outreach programmes to business schools.

The issue of fund size also came up – the comparison was made between larger funds and smaller funds, such as Beringea, represented by Karen McCormick. Larger funds have the upper hand when it comes to accommodating maternity (and paternity) leave, as there are more people around to share responsibility and maintain deal flow – vital to ensuring investment targets are met for LPs. It’s much harder to share the load in a smaller fund. As a point of interest, Beringea has a 50% representation of females at the senior level (three out of six).

Marijana Kolak of Bain Capital, one of the 20% of firms with senior female representation, summed up the entire issue very succinctly by remarking that one way of making progress would be to create a culture where fund leadership is comfortable with talking to female professionals about the issues that arise in planning their careers, and being able to address those in a customised way. In her experience, such atmosphere has given confidence to young women – and men – that they can have a successful long-term career with the firm.

Jeryl Andrew has a difficult task ahead of her, and a goal which will take a lot of effort to achieve. Environmental, Social and Governance issues have risen up on GPs’ agenda because more and more LPs are asking relevant questions, with investment decisions influenced by the answers. Gender opportunity questions have also started appearing on DDQs – perhaps the same trajectory of importance will start being given to the issue when investment decisions are affected by the answers.

It will take the entire industry to get on board to meet Level 20’s goal of 20% of senior positions in funds filled by women. Although, as Gail points out it, it would only take each of the 100 funds in our survey hiring one female into a senior position to reach that 20%, so maybe everyone should just start with one…

*Data from Hampton Alexander Report

About the author: John Cockburn joined PER after nine years as an officer in the British Army. He now works on placing people into investment, IR and origination roles across the middle market.

Gender Diversity Debate

27 Oct 2016

PER has recently conducted some research into gender diversity across job role, level of seniority and fund size in private equity. Whilst you are unlikely to be surprised, we think the hard facts bring home the issue: in summary, about 16% of investment professionals overall are female, however most are at the junior levels and female representation at director and partner level is generally less than 10%.We are seeing private equity doing a great job at pushing up the numbers of females when hiring. The next step may be harder: retaining and promoting them into senior positions.

We are continuing to push forward the debate and would be happy to share the collective knowledge we have on the subject gathered from across our client base and from the many females that we have placed in private equity roles. This year to date we have included 500 females on shortlists and 50 of them have received offers so far.

We have organised a breakfast workshop on the 24th November with Jeryl Andrew, the new CEO of Level20 as our guest speaker. Please contact events@perecruit.com if you would like to join us.

Look before you leap: Should you really ditch investment banking for private equity?

13 Oct 2016

By Paul Clarke efinancial careersJunior investment bankers in IBD are gaming their careers these days and, for most, it’s a simple track. Spend a couple of years at a bulge bracket bank, clock the hours, acquire the skills and then move into private equity.

In fact, of the analyst class to join in 2012, 55% made the switch across to the buy-side within two years. And, while IBD generally is the primary target for PE recruiters, it’s the leveraged finance teams of investment banks that see the biggest exodus.

For Ben Thompson, a managing director in J.P. Morgan’s high yield and leveraged loan capital markets team who has also spent some time in PE, this is a source of frustration. It’s also, he suggests, not always a wise move for a junior banker.

“There’s a blurred line between leveraged finance teams and private equity firms. They can be, in some cases, clients, partners or competitors,” he says. “They love to hire juniors from investment banks, because they’re well trained and have the sort of background they’re looking for.”

PE firms don’t have to work hard to attract juniors, and usually only the very best make the cut. “Private equity firms have a good head-turning pitch,” says Thompson. “Come here, you’ll be part of a small investment team, see the whole deal process and get access to senior management.”

“That can work for some people,” he adds. “I’ve known people who have switched across at the right time, managed to move up the ranks and it’s worked for them. However, I’ve had conversations with other juniors who have told me that, honestly, the work is essentially the same – just from the other side of the table, the hours aren’t much better and the pay is on a par with investment banking. And I certainly see juniors here getting daily exposure to the most senior members of the firm.”

Private equity firms don’t pay that much more to their juniors than investment banks. An associate in private equity earns at least £150k in total compensation, according to research from recruiters Kea Consultants. An equivalent role in an investment bank pays an average of £145k, but it varies between firms – J.P. Morgan pays the most, according to recruiters Dartmouth Partners.

“The hours really aren’t that much different from investment banks at large private equity firms, and compensation can be on a par with banks – or even lower,” says Gail McManus, managing director of Private Equity Recruitment. “But people don’t move for the cash, and longer term it can be more lucrative. In my experience, people rarely move back to banking.”

The logic is simple, she says – if you have any ambition to work in private equity, the window of opportunity is tiny. Most people she encounters realize that they don’t want to work in banking forever, but if they leave it too long they will never have the chance to switch to the buy-side.

“By the time you’ve reached VP, you’re stuck,” she says.

It’s easy, of course, to bash investment banking careers and the sell-side’s struggle to keep hold of millennials is well-covered. But are there genuine reasons for sticking around?

“Our counter-pitch is that we’re a global organisation with a huge array of opportunities,” says Thompson.

People at J.P. Morgan have joined the leveraged finance team from debt capital markets or investment banking coverage teams in the past few months, he says. Right now, an associate working in its London levfin team has just switched with a Chicago-based junior for a year.

“Juniors should be able to have an honest conversation with their manager, who can talk through what opportunities are available to them,” he says. “I’ve been in leveraged finance for many years, but started out in the Telecom Media and Technology investment banking coverage division. There are a lot of cool opportunities within the IBD or the broader firm.”

But McManus says that aside from progressing up the ranks, there’s a clear career path for juniors who have made the switch across to the buy-side.

“The hours and the culture at mega-firms can be very similar to large investment banks,” she says. “So, more often, juniors spend a couple of years at a large firm, get the brand name on their CV, and then move to a mid-market firm. There the deal exposure is greater and you can really start to make your mark.”

By Paul Clarke, eFinancialCareers

Gail McManus listed in Real Deals “The 20 Most Influential 2016"

27 Sep 2016

Our very own Gail McManus has been named number 15 in the list of individuals exerting the most influence over private equity for 2016.Real Deals say ""If you want a job in private equity, call Gail McManus" is the accepted wisdom across much of the industry. PER’s strong position in the recruitment market means that McManus has become one of private equity’s key kingmakers, opening doors for the industry’s most ambitious and capable."

Gail is renowned for her enthusiasm to share her views on private equity, including the importance of diversity, and women in senior roles within private equity.

PER speaks to FINANCE-TV

15 Sep 2016

Nadja Essmann, PER's Head of CFO Practice, recently spoke to FINANCE-TV about the importance of knowing the requirements of management teams when appointing a CFO.Nadja discussed the role of the CFO in private equity-backed portfolio companies. In addition she also discussed the differences between working in a family-run business compared to a listed company. She was able to give some insight into the career prospects, compensation structure and expectations that a private equity backed company CFO can expect.

If you are interested in finding out more details about CFO roles within the private equity industry please contact Nadja on nadja.essmann@perecruit.com

If you are interested in finding out more details about CFO roles within the private equity industry please contact Nadja on nadja.essmann@perecruit.com

London Firms Widen Their Search for Bigger Offices; Larger funds mean growing teams and demand for space

27 Jun 2016

Mayfair’s swanky private members’ clubs may find they have fewer private equity executives in the coming years.It’s not because buyout firms don’t like the clubs or the area. It’s because many private equity firms are being forced to look beyond their traditional stomping ground because they have outgrown their current office space.

Many private equity firms now require bigger offices because they are hiring bigger teams after a bumper few years for fundraising. But they are finding that space is hard to come by in the crowded Mayfair district.

The Carlyle Group is one such firm that is moving out of the area. The firm has agreed to take on about 63,000 square feet in London’s St James’s in a development that has a 40% larger floor area than Carlyle’s current base in London’s Berkeley Square. The Ontario Teachers Pension Plan moved out of Mayfair and across town to Portman Square, north of Oxford Street, when it made its move in 2015 – taking on more space in the process.

And those firms are not alone. James Fairweather, a partner at estate agent Knight Frank, said he had seen several private equity firms moving over the past year because they needed more space.

“The established ones are growing,” he said. “We’ve seen a number of clients telling us they are growing or they can see themselves growing and they’ll need more space. It’s all positive news.”

Overall, 21 private equity firms took new office space of about 337,000 square foot in London in 2015, the highest number of moves and total amount of space taken by private equity firms in the capital on record, according to research by Cushman & Wakefield for Private Equity News.

The offices were larger than in previous years, with firms taking on around 16,000 square foot on average in 2015, compared to an average of 10,500 across the previous eight years. And 2016 looks like it will be another strong, although not record breaking, year. By mid-June private equity firms had taken on around 69,000 square foot of new office space in London – around 13,800 square foot on average.

The need for larger offices is in part driven by fundraising and also firms getting into new business lines, such as private debt and special situations.

Private equity firms have had a record few years for fundraising, and those bigger pools of cash usually mean they have to increase the size of their teams to help them source deals. Europe-focused funds raised an aggregate €128 billion in 2015, the highest level since 2007, according to data provider Preqin. The size of the average fund also increased, from €404 million in 2014 to €594 million in 2015.

Expansion mode

Charlie Hunt, a principal consultant at headhunter Private Equity Recruitment, estimates that there are about 6,000 people working in the buyout industry in London. He said that many firms were in expansion mode, partly because they were raising bigger funds, so needed more staff to either complete a higher number of deals or bigger transactions.

“The funds that are growing are hiring more people,” he said. “You need more people to do the bigger deals because you are going in to just more complexity on the bigger transactions. So you may have teams of people just doing the banking, or just doing the insurance, etc.”

Robert Swift, a partner at mid-market firm Stirling Square, said that his firm was moving to bigger offices in Chelsea because “the team has grown since the final close of our third fund” – a €600 million vehicle that closed in January. A person close to Advent said the firm was moving to the Nova South development in Victoria because it had a break clause on its current building in Victoria and it had also increased the number of staff in its office.

A person familiar with Oaktree Capital said that the firm was moving in to a 38,000 square feet development in the Verde development in Victoria from its current base in Knightsbridge because the firm had expanded in recent years.

The demand for bigger space is compounded by the fact that private equity firms typically take up more space than their peers in other sectors of financial services.

A private equity firm will usually budget to have around 120 square feet per person, whereas a typical hedge fund would budget for around 100 square feet per person, according to property consultants. That’s because senior executives in private equity firms often like having their own private office, with junior staff members either working in open plan or sharing offices. They also tend to need more space for meeting rooms to accommodate lawyers, bankers and management teams when a deal is getting done.

Alongside the demand for more space, property consultants report that buyout firms typically want offices with roof terraces, natural light and all their staff on one floor. Such demands are difficult to accommodate in crowded Mayfair, where many buildings are former residential buildings that have been converted into offices. Mr. Fairweather said: “Natural light is key. They are not so much like hedge funds, which are more open plan. They are needing more private offices and they want to be on less floors.”

One of the most popular areas for private ¬equity firms seeking a bit more space is nearby St James’s, but Victoria, north of Oxford Street and even Soho – all areas near Mayfair – are now options for a new location.

Victoria and North of Oxford Street have the added bonus of being a bit cheaper than Mayfair and St James’s. North of Oxford Street and Victoria locations typically command rents of around £82 per square feet, compared with about £130 per square feet for Mayfair and St James’s for newly refurbished offices, according to a report by Carter Jonas in June. For those that are willing to head to Holborn and Bloomsbury, rents fall to around £67 per square feet and to £65 per square feet in the City core.

No price worries

However, property consultants report that private equity firms are not usually worried about the price tag. Elaine Rossall, head of research at Cushman & Wakefield, said: “Mayfair and St James’s will still always attract a certain kind of financial services company. Property overall is still a very small part of their costs, so they can afford to be in some of those prime locations but you have seen some of the financial services companies moving to north of Oxford Street and to Victoria.”

But one nearby area does appear to be out of bounds. Private equity firms are being squeezed out of Knightsbridge, mainly because many smaller offices have been turned into high-end homes.

Patrick Ryan, a partner at property consultants Levy, said: “The smaller office units have now been switched to residential in Knightsbridge. That has severely reduced the number of options available to small private equity firms in Knightsbridge. There is little or nothing over there.”

By Becky Pritchard, Private Equity News

Private-Equity-Manager werden immer öfter CFOs

08 Jun 2016

Finanzinvestoren kaufen immer mehr kleine Firmen auf. Den alten CFO müssen sie danach meist austauschen, sagen die Headhunter Rupert Bell und Nadja Essmann. Nachschub suchen sie zunehmend in den eigenen Reihen.Finanzinvestoren haben ein Auge auf kleine Unternehmen geworfen. Denn die Konkurrenz am M&A-Markt ist geringer, und die Unternehmensbewertungen dadurch niedriger. Diese Tatsache ruft neben neuen Spielern auch erfahrene Private-Equity-Häuser auf den Plan. So hat zuletzt die schwedisch-britische Beteiligungsgesellschaft IK Investment einen Smallcap-Fonds aufgemacht.

Das gesteigerte Interesse an dem Segment stellt die PE-Häuser vor eine Herausforderung: Sie brauchen Finanzchefs, die sich erstens für die Aufgabe eignen, die zweitens Lust auf die strapaziöse Zusammenarbeit mit einem Investor haben und denen drittens das Portfoliounternehmen nicht zu klein ist.

Einfach den bisherigen CFO im Amt zu lassen, funktioniert in den seltensten Fällen, erklärt Rupert Bell. Er leitet aus dem Münchener Büro des Headhunters PE Recruit dessen Geschäfte im deutschsprachigen Raum. PE Recruit ist auf Personalvermittlung für Finanzinvestoren spezialisiert.

Investoren tauschen den CFO meist sofort aus

Kleine Firmen in Unternehmerhand vernachlässigen die CFO-Position oft, begründet Bell seine These. „Selbst der Vertriebs- oder der Technikchef bekommt mehr Ressourcen.“ Das Finanzmanagement in kleinen Unternehmen beschränkt sich oft auf Grundlagen wie Buchhaltung und Controlling.

Sobald Private Equity einsteigt, gewinnt der Finanzchef dagegen schnell an Stellenwert. „Wenn ein Investor ein Unternehmen mit 50 Millionen Euro Umsatz übernimmt, denkt er schon an die Zeit, in der die Firma möglicherweise einmal 200 Millionen Euro Umsatz generiert“, sagt Nadja Essmann, die bei PE Recruit im deutschsprachigen Raum für die Suche nach CFOs zuständig ist.

„Der CFO ist nach dem Einstieg eines Investors in einer ganz anderen Rolle“, sagt Bell. „Da geht es nicht mehr nur um technische Angelegenheiten, sondern der Finanzchef muss dem Management und den Investoren als Sparringspartner dienen.“ Außerdem liege es am Finanzchef, im Auftrag des Mehrheitseigners ein schnelleres und präziseres Forecasting und Reporting auf den Weg zu bringen. Die Folge: Nach mindestens zwei Drittel der Transaktionen tauscht das Private-Equity-Haus den CFO sofort aus, schätzt Bell. Dazu kommen die Fälle, in denen der Finanzchef gehen muss, nachdem etwas schiefgelaufen ist.

Carlyle-Manager Dennis Schulze wurde Douglas-CFO

Die Beteiligungsgesellschaften haben also einen hohen Bedarf an CFOs für ihre Portfoliounternehmen. Doch Finanzvorstände und -Experten ohne Private-Equity-Erfahrung kommen aus ihrer Sicht von vornherein kaum in Frage. Das führt dazu, dass die Beteiligungsgesellschaften immer öfter bisherige Investmentmanager von sich oder von der Konkurrenz als CFOs einsetzen. Bell: „Private-Equity-Manager werden immer öfter CFOs. Sie haben die Herangehensweise eines Generalisten, kennen den Exit-Prozess, und sie wissen, worauf der Eigentümer hinauswill.“

So machte etwa der Midcap-Investor Chequers 2011 Eric Oellerer, vormals bei HG Capital, zum Finanzchef des Werkzeugherstellers Metabo. Das baden-württembergische Traditionsunternehmen ging vor einem halben Jahr an den japanischen Konzern Hitachi, Oellerer ist immer noch an Bord.

Ein Beispiel aus dem Largecap-Segment: Advent International warb 2013 den Deutschlandchef von Carlyle, Dennis Schulze ab, damit dieser als Douglas-CFO den großangelegten Umbau der Kette begleitet. Schulze machte 2015 für seine Nachfolgerin Erika Tertilt Platz.

Weil der Private-Equity-CFO so eine aktive und anspruchsvolle Rolle einnimmt, ist der spätere Wechsel auf den Chefsessel nicht unrealistisch, sagt Bell: „Wenn es klappt, kann der CFO eines Portfoliounternehmens mit 50 Millionen Euro Umsatz nach fünf Jahren zu einer 300-Millionen-Firma wechseln. Der nächste Schritt kann in der Ordnung von 500 Millionen liegen. Und dann liegt der Schritt zum CEO nahe.“ Eine Perspektive, die ehrgeizige Private-Equity-CFOs motivieren dürfte. Und ohne eine große Portion Ehrgeiz ist es ohnehin keine gute Idee, unter einem Investor den Finanzchef zu machen.

By Florian Bamberg, www.finance-magazin.de

Why private equity firms need to be more like investment banks – and fire people

01 Jun 2016

Private equity is supposed to be the promised land. Spend a couple of years in the tumultuous world of investment banking, before beating the (stiff) competition for a move to the buy-side for more pay, better work life balance, and – importantly – job security.Private equity firms rarely fire people, and lock senior staff in with carried interest that is simply too good to walk away from. But what if they’re all doing it wrong?

A new study by academics at London Business School, Saunder School of Business, and the University of British Columbia challenges the notion that team stability is important for private equity firms’ performance. Firing under-performers and bringing in new blood to adapt to a changing business environment is exactly what private equity firms need, it says.

It has come to this conclusion after examining a hefty 138 firms, 5,772 deals in around 500 companies and 5,926 people over 20 years.

“Contrary to the belief among private equity investors that turnover is disruptive, our results suggest that turnover has, on average, a positive effect on PE performance. Thus, this obsession with team stability may be unwarranted,” it says.

Stability is over-rated

If a key individual leaves a private equity firm, chaos ensues. The firm freezes fund-raising efforts and new deals are non-existent as the firm works out how to untangle the often 20-year career of a private equity partner.

“Partner to partner moves simply do not exist,” says Gail McManus, managing director of Private Equity Recruitment. “They have carried interest tied up in at least three funds, so have too much to lose. The only way they keep it is by being a ‘good leaver’ – that means cutting a deal to keep the carry, not working anywhere for 12 months and never working for a competitor.”

The study pointed to how private equity funds boast of ‘stable’ teams in order to impress and attract investors. The contrast with investment banks could not be more apparent. Investment banks have plenty of ‘lifers’, but they also cull the bottom 5% of under-performers annually as a matter of course and fire decidedly more than that when the business environment turns sour – like now.

As a result, junior bankers have been clamouring to get to the buy-side – often negotiating offers just six months into their banking career – and are leaving for a PE role ever-earlier.

The junior churn

More private equity firms are offering analyst programmes and recruiting graduates straight out of university (normally straight-A students with a couple of banking internships). It’s here where the fall out is.

“When I got promoted to associate, I knew I was in a stable job,” says one private equity associate who was promoted last summer. “Up until that point it’s like a temporary contract – you have two years and there’s no guarantee you’ll make the cut. Around 30% of people don’t.”

McManus says that a lot of private equity firms hire associates for two or three years with no promise of a job at the end of it. “Even then, it’s not so bad – it’s not like being fired really. You have a large private equity firm on your CV and you can easily get another job at a mid-market firm or even a competitor.”

The study suggested that the average age of people on deal-making teams was 37.42 and that the average experience level is 6.03 years. 29% of these people had an MBA (and 81% of these from a top business school), but financial sector expertise (48%) was by far the most prevalent skill.

“These results suggest that what matters in the long-run is not hiring individuals who can better restructure existing investments, but rather hiring individuals who bring in fresh ideas and skills to the team, or who are better suited to source and run new investments,” it says.

The study ran over 20 years, but McManus says that moves are more prevalent in private equity these days anyway: “Juniors have more selectability and are not tied to one organisation. Most people have three or four moves on their CV now and it’s not frowned upon as it was before the financial crisis.”

By Paul Clarke, eFinancialCareers

Succession: what private equity can learn from Clessidra The crisis the Italian firm has faced illuminates an industry-wide problem.

04 May 2016

It could almost be the plot of one of Italian cinema’s famous melodramas. Claudio Sposito was born in Rome in 1955, trained as an architect, then moved into finance where he was dubbed “a whizz-kid banker” by the Economist, spending ten years as Morgan Stanley’s head of Italian investment banking activities and chalking up stints at Barclays, Citibank and Standard Chartered.After going on to supervise the IPO of the Berlusconi family’s media group Fininvest, he founded Clessidra Capital Partners in 2003 and over the next decade built it into one of the Italian market’s top private equity firms.

With a widely envied network of contacts in Italian business and an ability to write cheques much bigger than most others in the market, Clessidra backed high-end jeweller Buccellati in 2013, flamboyant clothing brand Roberto Cavalli in 2015 and, alongside global giants Advent International and Bain Capital, took over banking group ICBPI in a multibillion euro deal last June.

Alongside these headline-grabbing transactions, the firm also made a steady series of investments in Italy’s strong industrial, manufacturing and food and drink sectors.

It wasn’t always la dolce vita, though. Clessidra made no investments between 2009 and 2012 and had to cut a planned fundraise from €1.4bn to €1.1bn in 2013 after investors voiced concerns about the firm’s ability to deploy capital.

But it could be argued that these difficulties stemmed from the global financial crisis and the consequential impact on Italy’s economy as a whole. By 2015, Clessidra was in the market again and, as reportedly one of the most popular firms in Europe with investors, seemed firmly on track for a successful raise and further blockbuster investments.

Sposito’s sudden death in January 2016 after a short illness changed everything. Without its founder and leader, Clessidra found itself with its key man clause breached, its fundraising effectively put on hold, and its future uncertain, as Sposito’s widow tried to dispose of her late husband’s 79 per cent stake in the firm.

Talks with new chair Francesco Trapani fell through in March after the parties failed to agree satisfactory terms. Following this news, a deal with an external investor looked like Clessidra’s only option for any kind of swift resolution. Coller Capital and Neuberger Berman were mentioned in the market as potential buyers, but at the time of writing it appears that Italian financial conglomerate Italmobiliare will prove the firm’s saviour, having entered exclusive negotiations to acquire 100 per cent of the GP.

This or any other deal will, however, be conditional on a potential investor’s confidence in the stability of Clessidra’s current team. The departure of two partners this month, and rumblings that others might follow, throws this into doubt.

“It would have been easier if the firm could have come to a solution internally rather than having to go into a sales process,” says a GP familiar with the Italian buyout market. “It’s tough. Where do they go from here? [An external deal] looks like a possibility. But it will all depend on the price and making sure that the team will stay on.”

A deal will also be dependent on the confidence of a potential new investor that Clessidra’s team can continue to raise and deploy money. The firm is thought to have raised €500m and reached a first close of its new fund, but commentators agree that to all intents and purposes this process remains in limbo until the ink on any deal is dry and, as one placement agent points out, all commitments made so far can be regarded as effectively cancelled thanks to the key man clause breach caused by Sposito’s death.

In addition, Clessidra was until very recently a beneficiary of the shift in the LP community towards a preference for fewer, stronger relationships with premier GPs. But now it faces the flipside of this trend and the fact that there are a number of other Italian firms that, if smaller in scale, still offer investors attractive exposure to an Italian economy that is strengthening and remains underpenetrated by buyout investors.

The prospect of future deployment by Clessidra, meanwhile, comes back to the success or otherwise of this current fundraise as Fund II, closed back in 2009, is nearly exhausted.

“This a good firm with a strong brand. They should be back to business as normal once the sale is finalised,” says one GP who has invested in Italy. Others in the market are less optimistic.

And even though Italmobiliare’s interest is ostensibly good news for Clessidra, it is worth noting the investor’s references to “strengthen[ing] [Clessidra’s] management structure” and “contributing [Italmobiliare’s] own industrial management vision”.

This suggests that Clessidra’s team, identity and way of working may all be up for debate once the firm and its assets are the hands of its new owners.

What went wrong at Clessidra

“Clessidra, the Italian word for ‘hourglass’, the ancient instrument that measures time with the constant flow of sand, reflects Claudio’s belief that value is created over time,” reads Clessidra’s website. Unfortunately, without Sposito, it appears that value is also at risk of flowing away very quickly.

“This is a good example of the perils of not doing proper succession planning,” says Sunaina Sinha, managing partner at Cebile Capital. Commentators agree that Clessidra’s current difficulties stem from the firm’s failure to build an institutional identity and infrastructure that could operate confidently in the absence of its founder.

“The succession issue has been a difficult one [for Clessidra],” says one GP familiar with the Italian buyout market. “Claudio Sposito was such a respected and charismatic leader and it was always going to be difficult to follow him.”

Rupert Bell, principal consultant at Private Equity Recruitment, describes Sposito as a “a very senior and successful investor”, and adds that “mid-market firms are often built in the shadow of one particularly strong leader” so “for all that people talk about equality of partners”, they can find themselves in “an Animal Farm-type situation, where some ‘animals’ are much more ‘equal’ than others. And when a person like that disappears, that exposes certain structural weaknesses.”

The problem is worsened by the fact that not only had Sposito not anointed a second-in-command and heir clearly enough, but that the main candidate for this distinction, Trapani, is widely seen as an outsider to the firm and the industry itself. He joined Clessidra in 2014 as an operating partner after a career with his family’s jewellery and watch business Bulgari and then at luxury group LVMH, which bought Bulgari in 2011.

“It was silliness to identify a successor who wasn’t really one of them,” says one person familiar with the Italian private equity market. "Why bring in a ‘foreigner’? It’s a complex enough situation.”

One Italian GP commenting on Trapani’s appointment says that in private equity “it’s a completely different situation when you create and develop a team to when you come in later as the boss”, while another dealmaker familiar with the market thinks that “it must be tough for Trapani, who only joined around two years ago, to step into those big shoes and maintain the spirit of the firm, especially in such sad circumstances”.

Others lament the fact that Clessidra did not take sufficient precautionary steps in 2015 once the imminent coming of the sad situation it was shortly to face must have become clear.

“As soon as Claudio knew he was ill, a full transition process should have been put in place”, transferring leadership and also ensuring Sposito’s shares would be sold at a good price and in a way that would enable the business to continue with minimal disruption, says Giacomo Biondi Morra di Belfort, managing partner of Capstone Partners.

He adds that he thinks that doing so, even late in the day, could have avoided what have been difficult and prolonged negotiations around Sposito’s interest in the firm.

A time bomb for the private equity industry

It is worth noting that the situation faced by Clessidra in recent months came to an organisation widely regarded as strong and resilient. “The firm was well-liked by investors and had good deals and a good bench,” says Mounir Guen, chief executive of MVision. “I would not have predicted this for Clessidra.”

In this light, any private equity firm under the assumption that its organisation is not at risk could be in for a rude awakening. The importance of planning well for succession is not an issue just for Clessidra or Italian investors, but applies across the buyout industry.

“A lot of firms do not do as good a job as they need to do to make sure that there is a good succession plan in place,” says Sinha.

Caroline Sage, chief executive of KEA Consultants, sees the issue as one inherent to the way firms were created and have grown, often focused around strong characters reluctant to cede control.

“For quite a while,” she says, “people who founded funds saw themselves as investment vehicles and not companies, so very little was done around culture or retention [of promising junior staff].” She adds that many firms, especially smaller ones, are still not doing enough to address this.

Bell sees the issue as nothing short of a time bomb for private equity, given that many founders and senior figures are approaching retirement age. Looking on the bright side, he adds that succession can be an opportunity as well as a risk. In the current environment where many GPs are struggling to stand out in a crowded, competitive market, having a good succession plan could come to be a valuable differentiating factor.

How to future-proof your firm

“Write a will,” is one placement agent’s succinct advice to firms hoping to avoid Clessidra’s fate, or to use future-proofing. “As a firm whose business is assessing risk in target investments,” says Bell, “you need to apply that discipline to yourself, otherwise you run the risk of losing everything, not least the support of your investors.”

The first practical step firms should be taking when considering succession is simply discussing it because, Bell says, even “having it as a non-taboo subject” can be tough for some houses where “there’s so much influence and control with one individual that even asking the [succession] question seems like an internal challenge, which needn’t be the case”.

A crucial further step is to put time and effort into supporting the next generation. “You need to have a sense of a developing second tier management coming through with the incentives and rewards to structure that not just for two years but for two fund cycles,” says Bell.

This point is particularly prescient given that a working paper published this month by Josh Lerner and Victoria Ivashina of Harvard Business School found that fund economics are typically weighted toward founders, with the individual performance of more junior partners having little influence on remuneration.

In addition, it is neccessary for LPs to become comfortable with the idea of a changing of the guard. “If they are still totally bought into the founders, and that’s why the money comes in every time they fundraise, then that’s one thing that you have to tackle first, passing over relationships and that belief,” says Sage.

Ultimately though, Bell thinks the issue is philosophical as well as practical. Successful succession planning is about “a certain forward-thinking mentality, or a generosity of spirit, or just having a diversity of other interests beyond the business [that enables some founders] to say: ‘I’ve built something interesting and it’s now time for this to move on without me.’"

"They may keep their name on the letterhead, turn up for investment committee meetings, or preserve a mentoring influence, but they recognise that if the firm is to have a future they have to enable that by creating space for the people behind them,” he says.

But, in Bell’s opinion at least, it is unfortunate for private equity that when it comes to the industry’s big characters, “this is not how many of them tick”.

by Hannah Langworth, Real Deals

When’s the best time to quit banking for Carlyle, KKR or TPG?

28 Apr 2016

You’re fed up with being an analyst or associate in an investment bank. Like every other junior IBD professional, you want to move to the buy-side. – Specifically, you want to move to private equity. So, when’s the best time to quit?We looked at 30 former investment bankers who left a variety of leading investment banks for three top private equity funds in London – Carlyle, KKR and TPG. The takeaway? Most people who quit banking for private equity do after 24 to 34 months in IBD.

Charlie Hunt, principal consultant at PER, a private equity recruitment firm, said you might even want to leave earlier: “You ideally want to leave sometime between being a second year analyst and first year associate.”

If you’re going to quit for private equity, you need at least one year’s deal experience, says Hunt. Although we came across assorted people who quit banks like Goldman, Morgan Stanley and Credit Suisse for KKR with anything from 49 months to 60 months’ IBD experience, Hunt says the move across becomes harder the longer you leave it. “It’s more of a gamble when you wait. Moves at that level usually only happen when you know someone in the fund,” he said. Most of the people moving across with that level of experience joined as principals rather than associates.

Of the three firms we looked at, one seems to prefer its associates with a little more experience than others: KKR. On average, KKR’s associate hires have three years’ investment banking experience, compared to closer to two and a half at Carlyle and TPG.

While leading private equity firms like to hire from leading banks, they seemingly like to hire from one bank more than the rest: Goldman Sachs. – Around 40% of the associates in our sample worked for Goldman before making the move.

by Sarah Butcher, eFinancialCareers

CFA, MBA, Masters, CAIA, ACA or PhD: What do private equity firms want?

28 Oct 2015

Private equity firms like to hire winners. They want the elite investment bankers and graduates who can demonstrate the sort of qualities that will set them apart from the 300 other applicants.This also means getting a top class degree from the ‘right’ – read top – university. But an undergraduate degree is one thing. How will professional qualifications and masters degrees help your chances?

The biggest boon to a private equity job application, perhaps surprisingly, is a Masters in Finance degree. Our figures, based on the 1.2m people in the eFinancialCareers CV database, suggest that 28% of private equity professionals possess a Masters degree, compared to 26% with an MBA – the more traditional method of getting a private equity job.

“Masters in Finance degrees are increasingly important for securing an investment or reporting job in private equity,” says Gail McManus, managing director of Private Equity Recruitment. “MBAs are still important, but they need to be combined with experience – whether that’s PE or investment banking.”

Once again, the CFA also ranks relatively highly in the alternative investment sector. 19% of hedge fund professionals on our database have studied the CFA, and this figure is 17% in private equity.

“A lot of limited partner private equity firms will hire undergraduates and then put them through the CFA,” says McManus. “It’s rare for direct investment firms to do the same.”

McManus adds that UK private equity firms also tend to favour those with an ACA accounting qualification – who often come from the Big Four – largely because senior partners at these firms also possess the qualification. However, our data suggests that just 2% of private equity professionals have an ACA.

By Paul Clarke, eFinancialCareers

PER Sponsored Investor AllStars 2015

26 Oct 2015

PER were proud to present the prestigious Investor of the Year award at the 2015 Investor AllStars gala in London.The judges looked for evidence of the following:

• A strong network from which to source deals.

• An ability to assess opportunities, manage the due diligence process and close deals in difficult circumstances.

• A reputation amongst portfolio companies for providing valuable support.

• A significant role in driving the venture capital industry forward.

All the winners and those short-listed can be found at the following link - Investor AllStars 2015

Europe’s ‘Masters of the Universe’ Don’t Need Business Masters

17 Jun 2015

For future buyout kings in the US, an MBA is no longer a must-have. The qualification has also been losing its luster among financial institutions in Europe, according to recruiters and graduates.As recently as 2007 London Business School sent roughly half its graduates to financial institutions, but that number has fallen sharply and now stands at just over a quarter as tech companies recruit more heavily from business-school classes.

But headhunters also say the letters MBA on a candidate’s resume might not impress financial institutions as they once did: the qualification has become so widespread that it means little, especially if it is not from a top business school.

Logan Naidu, chief executive of U.K. recruitment firm Dartmouth Partners, said: “Do I think [MBAs] accelerate your career? The answer is no. I don’t think in financial services it’s very helpful. It’s rather like any qualification – it’s nice to have and, all things being equal, it might tip things in your favor but processes very rarely go down to the wire like that.”

Graham Beatty, executive search consultant at recruiter Russell Reynolds in New York, said that financial services firms on both sides of the Atlantic are putting more value on experience than in the past, even for junior roles, so people who might once have left a bank analyst program for business school might now be better off sticking around.

This is true even in fields such as venture capital, where nearly a third of executives have graduate business degrees, compared with about 12% in investment banking, according to a poll of more than 6,000 European finance executives by salary benchmarking website Emolument.com.

Gail McManus, founder of Private Equity Recruitment said that it was far more important for candidates to gain good experience in the right field rather than to get an MBA qualification. “What matters more than anything is what you did before your MBA . So if you didn’t get the right experience before your MBA , then the MBA isn’t going to solve it,” she said.

For those who do decide to pursue the degree, Joe Krancki, a partner at European growth capital firm Frog Capital and MBA from London Business School, says a business school’s network matters more than the coursework.

“I think the stuff you learn in the classroom, by and large, you can learn for free,” he said. “Why I think the MBA is still quite valuable and special is it gives you an opportunity to be surrounded by 300 or 400 exceptionally bright people who you can learn a lot from. They become friends and you can continue to collaborate and – it sounds bad – use each other.”

Andrew Breach, head of the banking and financial services practice at U.K. head hunter Page Executive, added that people should consider when they are likely to be in management ahead of doing the course as many of the skills it teaches could be less relevant to junior staff.

“If you do [an MBA] at 22 years old and you don’t manage people for [another] 20 years, then by the time you do, [the MBA] will be quite rusty. The bane of my job is when someone who is paid £50,000 at vice-president level all of a sudden wants £100,000 and to be a director. A lot of people are told they could double their salary just because they have spent a year doing an MBA. That’s not going to happen.”

By Paul Hodkinson, Financial News

Getting into Private Equity

13 May 2015

The perfect resume for breaking into private equityeFinancialCareers

There are many facets that comprise the perfect resume for breaking into private equity, but here’s the rub of the green – keep it short, keep it relevant, and make all your achievements tangible.

You will be up against hundreds of other applicants from the top investment banks and Big Four professional services firms and have a 10% chance of making it through to the first interview. Your CV is the first selling point – this is what you need to know.

1. The perfect private equity CV will be one page in length

Think you have enough skills and experience to run over two pages after two years working in the financial sector? You don’t. Private equity recruiters will give your resume around 30 seconds to impress, so it all needs to be immediately visible and easily readable.

2. A personal statement is a waste of space

Building on the demonstrating tangible achievements on your CV, a paragraph explaining your skills and career ambitions is way too fluffy to impress PE recruiters. “Never use narrative,” says Charlie Hunt, principal consultant at Private Equity Recruitment. “If you must write a personal statement keep it at four or five relevant bullet points.”

These could be:

• Your background, summarised and relevant to PE.

• Projects you have worked on relevant to the PE firm you are working on.

• Any relevant deal experience.

• Special academic achievements – assuming they demonstrate why you are an elite candidate.

3. The perfect private equity CV will focus on brand name universities

It’s something of a self-fulfilling prophesy, but private equity recruiters tend to hire people a lot like themselves. This means academically bright individuals who probably went to either Oxbridge, LSE or an Ivy League university and secured at least a 2.1, if not a first class degree or a 3.0 GPA.

4. When it comes to experience, deals are king

Having Big Four corporate finance experience or a top investment bank as your previous employer is more of a hygiene factor than a significant achievement. Your resume won’t even make it into a recruiter’s inbox without this. The next step is showing what you have achieved and this means relevant deals where your personal achievements are easily detailed.

“Just think of every relevant transaction or deal you’ve worked on and demonstrate what you’ve achieved,” says Hunt. “That can be due diligence, M&A, consulting or turnaround projects.”

5. The importance of personal interests

Because a lot of the private equity recruitment process is about finding the right fit as well as the relevant technical skills, showing that you’re a person worth talking to through your personal interests is important.

“If all you’ve got is gym, movies and reading, don’t put anything,” says Hunt. “Anything that shows you’re interesting – say, volunteering or charity work – is good, as are sporting achievements, but show that you’re a winner. One candidate put that they came second in a face painting contest to appear quirky, but the PE firm didn’t invite him to interview because he didn’t win.”

6. Other factors to consider in your private equity CV

Any evidence that you are a high achiever must be scattered within your CV without appearing overly boastful. Show that you are a top ranked analyst, or that you passed your accounting exams at the first time of asking, says Hunt.

Death of a Superhero

04 Feb 2015

Real Deals - Private equity's love affair with the cult of personality is losing its spark by Nicholas NevelingAt a SuperReturn conference in Berlin a few years ago David Rubenstein, one of the founders of the Carlyle Group, was scheduled to speak.

A few minutes before his slot, a large black sedan with tinted windows pulled up directly in front of the hotel and Rubenstein strolled out in a striking tan overcoat. He had barely stepped through the lobby doors when he was surrounded by journalists pushing recorders in front of him and asking about everything from deals to geopolitics. After his presentation, LPs were virtually queuing up to shake the Carlyle boss’s hand and slap him on the back as he headed for the exit.

It is not unusual for the media and investors to become star struck when encountering general partners like Rubenstein, who were doing deals when private equity was still in its infancy. KKR’s Henry Kravis and Blackstone’s Stephen Schwarzman provoke similar adulation.

And it is not just the founders of the US mega firms who have forged reputations as M&A celebrities. In Europe Advent’s David Cooksey, Apax’s Ronald Cohen and CVC’s Mike Smith have also inspired fascination.

There can be no doubt that the cult of personality has been a key narrative in the private equity story for the last 30 years. There is a mystique surrounding the buyout pioneers who oversaw the industry’s expansion from a small, obscure corner of financial markets into a multi-billion euro, global asset class. For investors the remarkable growth of private equity has been inextricably linked with the unique abilities of this elite class of seer-like Warren Buffet types.

Yet as crucial as the idea of a prominent individual has been for the asset class in the past, the way that private equity firms are led and managed is changing. The outgoing generation of managing partners are not handing over to a new group of anointed hero-leaders. Instead they are passing on the reins to triumvirates, boards and management committees. The asset class that was built around the triumphs of its founders is going all corporate.

“Back in the 1980s there were only a few pioneering souls in the industry and they dominated. They attracted a great amount of publicity and they were very influential. Now it is becoming less and less common to have a highly visible dealmaker,” says Better Capital founder Jon Moulton. “Do you know who is running CVC now that Mike Smith has retired? Do you know who the chairman of the BVCA is? I don’t. I can’t think of anyone under the age of 50 who is in the public eye and representing the industry.”

For Gail McManus, managing director of headhunter Private Equity Recruitment, this evolution has been inevitable given the asset class’s expansion.

“Funds are bigger. The amounts invested are bigger. GPs are not running €500m funds anymore, they are running billion euro funds. All of a sudden the industry has become much more complex and its impact greater,” McManus says. “One person, or a small group of people, can’t manage all of that alone. You need to build a corporate infrastructure. You need HR, finance and investor relations. Private equity firms are still full of entrepreneurial characters and they are still partnerships, but the success of a firm no longer rides exclusively on the performance of a small group of individuals.”

Read the full article on the Real Deals website

Private Equity Raises Pay to Lure Juniors in Hiring Spree

15 Dec 2014

Buyout firms are ramping up hiring of junior investment professionals and raising pay levels, after the strongest year for European fundraising since the financial crisis.According to a report from a recruitment firm, European private equity firms have increased their hiring of junior investment professionals by 40% over the past two years.

The research found that 139 junior executives moved into private equity from investment banking and consultancy firms in the 12 months to September, up from 99 in the same period two years previously. The figure is a slight increase on the previous 12 months, when 135 individuals made the move.

Headhunters attribute the increase to a buoyant fundraising market and improving economy, with firms looking to hire more juniors to help them spend their freshly raised funds. According to Preqin, more than 85 billion euros has been raised for 198 Europe-focused private equity funds so far this year, the highest amount raised for deals since 2008.

“We’ve definitely seen a lot of demand for junior level [staff],” said Charlie Hunt, principal consultant at Private Equity Recruitment. “The reason there has been more recruiting over the past 12 months is that more funds have been raised and existing funds are being successful. It means they are not trimming down their staff and are promoting people, which leaves a gap at the bottom.”

For more on how this new class of dealmakers is being compensated, and how that compares to other segments of the financial services industry, check out the full story in Private Equity News.

Write to Becky Pritchard at becky.pritchard@wsj.com

Follow her on Twitter at @beckspritchard

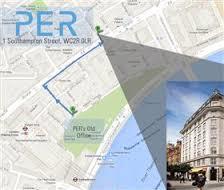

PER Moves to a New Office in London

24 Jul 2014

We've recently moved into our shiny new office in London.Our new address is:

Private Equity Recruitment Ltd

1 Southampton Street

London

WC2R 0LR

Our telephone numbers and email addresses have stayed the same.

We look forward to welcoming you in our new home.